With the explosive popularity and growing interest surrounding Black Myth: Wukong, now is the perfect time to reflect on the profound inspirations behind this journey. The game’s vivid portrayal of Sun Wukong has reignited my fascination with the legendary Monkey King and his epic adventures. As my childhood hero, Sun Wukong inspired me to embark on my own journey – leaving the familiar behind to explore the unknown West. While my travels may be more comfortable than his rugged quest, the spirit of adventure remains. Join me as I revisit the hero who sparked my own defiant, rebellious, and fearless fearful quest.

Journey to the West

Journey to the West [西遊記] is a classic Chinese novel written by Wu Cheng’en [吳承恩] during the Ming dynasty [1368 to 1644]. It’s one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature [四大名著] and is a fascinating blend of myth, fantasy, and adventure.

The Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature [四大名著]

- Water Margin [水滸傳] (circa 1524) by Shi Nai’an [施耐庵]、Luo Guanzhong [羅貫中] (Organ of authorship is subject to academic debate)

- Romance of the Three Kingdoms [三國演義] (circa 3rd century. 201 – 300AD) by Chen Shou [陳壽]

- Dream of the Red Chamber [紅樓夢] (circa mid-18th Century 1740s – 1764AD) by Cao Xueqin [曹雪芹]

- Journey to the West [西遊記] (circa 1592AD) by Wu Cheng’en [吳承恩]

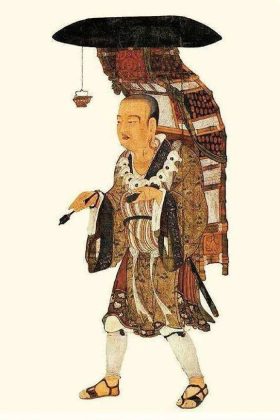

The story Journey to the West was inspired by the pilgrimage of the historical Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang [玄奘] [602–664 AD], who journeyed to India (referred to as the West) to retrieve sacred Buddhist scriptures.

In the novel he is known as Tang Sanzang [唐三藏] and also respectfully referred to as Tang Seng [唐僧]. Tang (唐): “唐” refers to the Tang dynasty, during which the story is set. This surname honours the historical Xuanzang [玄奘], a Chinese Buddhist monk who made a pilgrimage to India to collect sacred scriptures. Sanzang (三藏): “三” means “three,” and “藏” means “storehouse” or “scripture.” “Sanzang” refers to the “Tripitaka” which are the three collections of Buddhist scriptures: the Sutta Piṭaka (teachings of the Buddha), the Vinaya Piṭaka (monastic rules), and the Abhidhamma Piṭaka (philosophical and doctrinal analysis). Sanzang is a title that signifies his deep knowledge and mastery of these scriptures, marking him as a devout and scholarly monk on a quest to bring Buddhist teachings to China.

Accompanying him on this perilous journey are three disciples (fictional characters in the novel) :

- Sun Wukong [孫悟空] (The Monkey King) is a mischievous and powerful figure known for his immense strength, agility, and the ability to perform 72 Earthly Transformations [七十二变]. As the most iconic character from Journey to the West, Sun Wukong is famous for his rebellious nature and his magical staff, the Ruyi Jingu Bang [如意金箍棒]. His playful and cunning traits likely inspired the choice of a monkey for this character, along with possible influences from the Hindu deity Hanuman. or a Chinese monk Fajie [法界] (730 – 790CE), later known with the same name Wukong [悟空] .The name Wukong [悟空] combines “悟,” meaning “awaken” or “enlighten,” and “空,” meaning “emptiness” or “void.” Together, “Wukong” can be interpreted as “Awakened to Emptiness” or “Enlightened to the Void,” reflecting the Buddhist philosophy of understanding the emptiness of all things. The name signifies Sun Wukong’s journey toward spiritual enlightenment, despite his mischievous and rebellious nature.

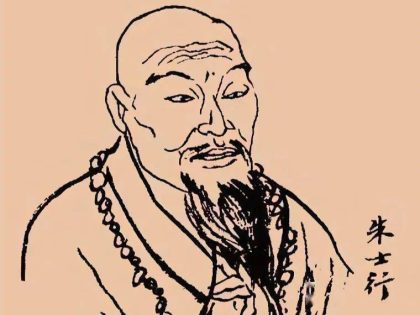

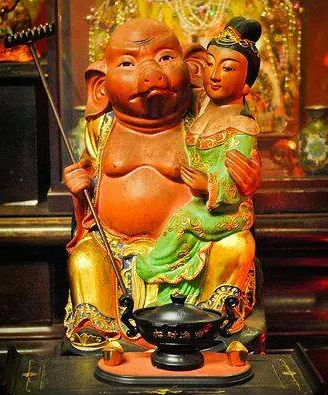

- Zhu Bajie [猪八戒] (Pigsy) is a half-human, half-pig creature with an insatiable appetite. Despite his flaws, including laziness and gluttony, Zhu Bajie remains a loyal and brave companion. Like the real pig, known for its voracious appetite and fertility, he symbolizes human greed and lust. Zhu [猪] means “pig,” The name Bajie [八戒] combines “八,” meaning “eight,” and “戒,” meaning “precepts” or “commandments,” referring to the Eight Precepts of Buddhism, which are ethical guidelines for living a moral life. The name is ironic, as Zhu Bajie often struggles with these precepts, particularly gluttony and lust, serving as a reminder of his need for self-discipline and spiritual growth. Zhu Bajie (Pigsy) in Journey to the West draws inspiration from the historical figure Zhu Shixing [朱士行], a Buddhist monk from the Han Dynasty. Zhu Shixing, also known by his religious name as Bajie, was the first Han-ethnic Buddhist monk who journeyed west to retrieve sacred sutras, an endeavour similar to Xuanzang’s pilgrimage depicted in the novel., a mission that predated Xuanzang’s famous pilgrimage by 400 years. His surname Zhu [朱] is merely homophones of Zhu [猪] for Pig. The character Pigsy mirrors Zhu Shixing’s quest and name, though not as far-reaching as Xuanzang, Zhu Shixing’s pioneering journey and role as the first Chinese monk to obtain sutras contributed significantly to his portrayal as Pigsy.

- Sha Wujing [沙悟净] (Sandy): A quiet and stoic character, who is the most level-headed of the group. He was a celestial general before being banished to Earth for breaking a vase belonging to the Jade Emperor. Sha [沙]: “沙” means “sand” or “gravel,” reflecting his association with the riverbanks and the sandy desert where he lived before joining the pilgrimage. Wujing [悟净]: “悟” means “awaken”, and “净” means “purity”. Wujing can be interpreted as “Awakened to Purity” or “Enlightened to Purity.” The name signifies his path toward spiritual purity and redemption. Unlike Sun Wukong, Sha Wujing is more serene and introspective, embodying the calmness that comes with inner purification.

Journey to the West is a rich narrative filled with encounters involving demons, gods, and mythical beings. These characters are inspired by Taoist deities, who embody natural forces and cosmic principles, and Buddhist figures, representing various aspects of enlightenment and moral teaching. The novel also integrates elements of local Chinese mythology, which brings a unique cultural flavour to the narrative. These encounters serve as tests of the protagonists’ resolve and morality, reflecting the novel’s allegorical themes. The story explores faith, redemption, and the struggle between good and evil, using fantastical elements to address profound philosophical and spiritual questions about perseverance and enlightenment.

The tale has been adapted into countless films, television series, and other forms of media, making it a significant cultural touchstone in both Chinese and global pop culture.

Uproar in Heaven

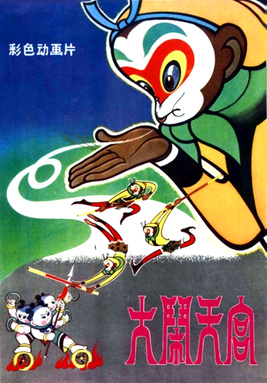

The one adaption that I grew up with is the animation The Monkey King: Uproar in Heaven [大闹天宫] by Shanghai Animation Film Studio released in 2 parts in 1961and 1964.

Uproar in Heaven [大闹天宫] follows the rebellious adventures of Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, who after seeking a powerful weapon, acquires the magical Ruyi Jingu Bang [如意金箍棒] (As-You-Will Gold-Banded Cudgel) from the Dragon King. His growing arrogance leads him to defy Heaven, claim the title of “Great Sage Equal of Heaven“ [齊天大聖] and cause chaos in the celestial realm. Despite attempts to subdue him, including being incinerated in Lao Tzu’s furnace, Wukong emerges stronger, ultimately defeating Heaven’s forces and returning triumphantly to his kingdom on the Flower and Fruit Mountain.

Now, imagine a monkey in the present day causing chaos in the Vatican or Mecca, then declaring himself an equal to their God, if not superior to their highest authorities. That’s my Wukong!

Video : Original Release (1961 Part 1 & 1964 Part 2)

Video : Remastered Release 2004 Part 1

Video : Remastered Release 2004 Part 2

Video : Journey to the West 1986 TV Classic Playlist

The Cultural Immortalization

Despite their fictional origins, the characters from Journey to the West have become deeply embedded in local culture, transcending the boundaries of myth and legend. Temples dedicated to Sun Wukong, in particular, can be found throughout Asia, where he is revered not just as a literary figure but as a deity of immense power and wisdom. His enduring legacy is a testament to the profound impact of the story, with Sun Wukong’s image immortalized in statues, artwork, and festivals.

Video – The Tâng-ki or Spirit-Medium of Qi Tian Da Sheng [齊天大聖]

A Tang-ki, or Spirit-medium, is a spiritual practitioner in traditional Chinese folk religion who acts as a conduit between the human and spirit worlds. During rituals, the Tang-ki enters a trance state, allowing deities or spirits to possess their body, through which they convey messages, offer blessings, or perform healing. This practice, deeply rooted in Chinese culture, is particularly prevalent in Taiwan and Southeast Asia, where mediums are respected for their spiritual insights and their role in maintaining the connection between the divine and the mortal realms.

Video – The Mantra of Sun Wukong

A mantra is a sacred word, sound, or phrase repeated in spiritual practices, often used in meditation or prayer to focus the mind and connect with the divine. Originating from ancient Indian traditions, mantras are believed to carry powerful vibrations that can bring about spiritual awakening, inner peace, or protection. In various religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, mantras are chanted to invoke deities, purify the mind, or manifest intentions, playing a central role in rituals and personal spiritual journeys.

In Taiwan, while Zhu Bajie is widely seen as the symbol of gluttony across China, he is also revered by sex workers under the title Shoushou Ye (授受爺). They offer him incense and prayers daily, asking him to bring wealthy, gullible clients to their doors.

Sun Wukong may have been influenced by local folk religion in Fuzhou, where monkey gods were worshipped long before Journey to the West. In particular, the Three Monkey Saints of Lin Shui Palace –Dan Xia Da Sheng [丹霞大聖] (Red Face Monkey Sage), Tong Tian Da Sheng [通天大聖] (Black Face Monkey Sage), and Shuang Shuang San Lang [耍耍三郎] (White Face Monkey Sage) – were once fiends subdued by the goddess Chen Jinggu [陳靖姑], the Empress Lin Shui [臨水夫人]. Due to the influence of Journey to the West, one of the main Monkey Sages has often been mistaken for Sun Wukong, also known as Qi Tian Da Sheng [齊天大聖].

Questioning the Boundaries Between Myth and Religion

Although I may not fully comprehend or disprove the existence of these fictional characters, their deep integration into culture and tradition is unmistakable. The reverence and enduring legacy that have been conferred upon them by countless generations make me reconsider the distinctions between established, institutionalized religions and these cultural practices. From a cultural perspective, I can only admire the profound influence these narratives have had, shaping beliefs and rituals that blur the boundaries between myth and reality. This leaves me questioning whether organized religion is fundamentally different from these practices, as both seem to stem from the same human need for connection, meaning, and belief.

Despite these reflections, I’ll simply embrace the enjoyment of the game and let the adventure unfold.

More Reads:

https://journeytothewestresearch.com